This Week on What the Hack: The Surveillance Economy

This Week on What the Hack: The Surveillance Economy

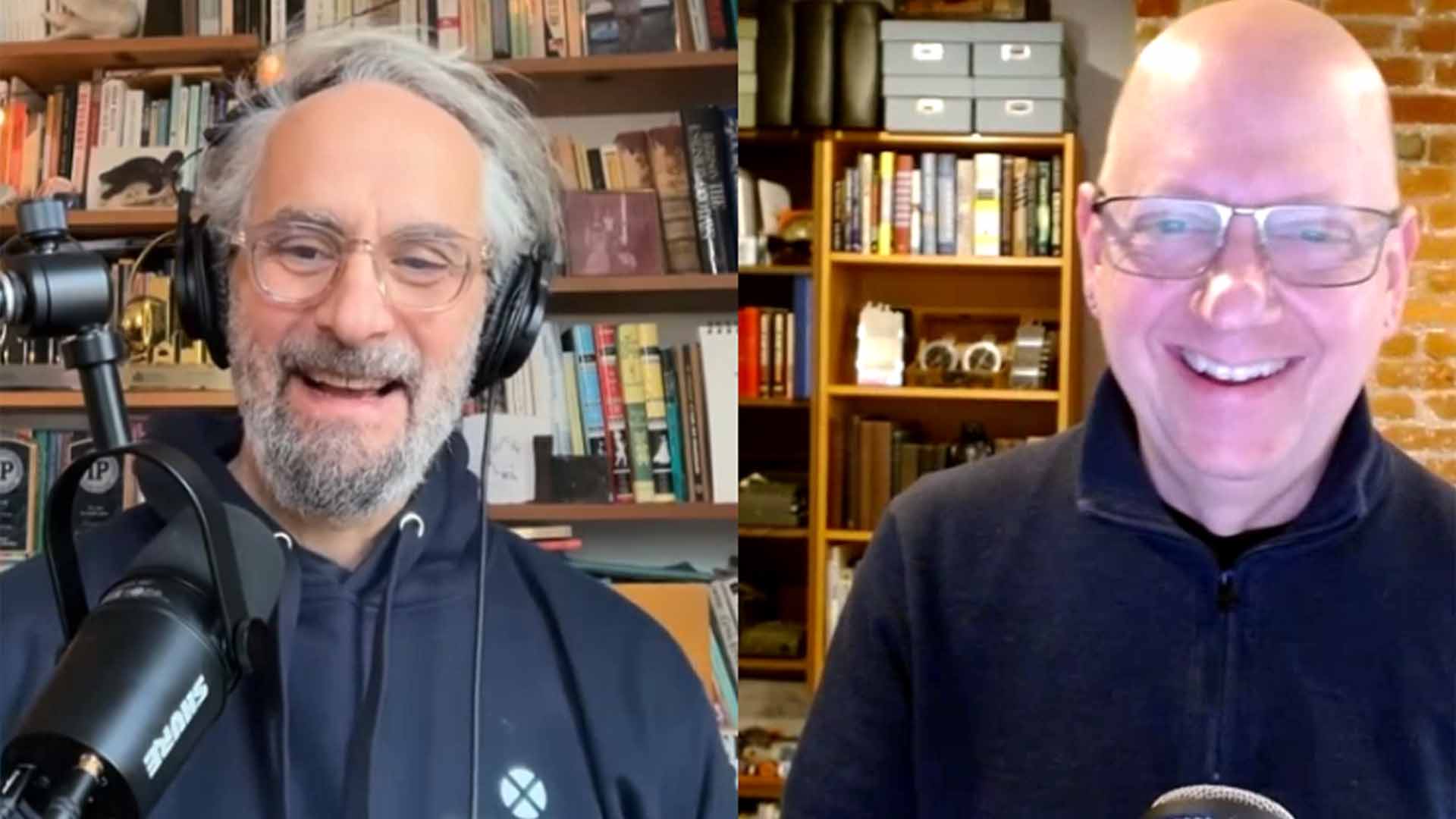

This week, we’re going to the movies. Virginia Heffernan joins us to talk about Groundhog Day (the movie), surveillance, and why online systems reward repetition over reflection with a special cameo by marketing maestro Seth Godin. https://virginiaheffernan.substack.com/

Episode 237

Ep. 237: “The Internet is Groundhog Day”

“What the Hack?” is DeleteMe’s true cybercrime podcast hosted by Beau Friedlander

Groundhog Day: Okay campers, rise and shine and don’t forget your booties because it’s cold out there.

Groundhog Day: It’s cold out there every day. What is this? Miami Beach?

Groundhog Day: Not hardly.

Groundhog Day: Nice going, boys. You’re playing yesterday’s tape.

Virginia: I thought I was pretty unfindable. I was extremely findable.

Beau: Virginia Heffernan. Writer, thinker, target. She’s not speaking in metaphors here. She’s describing what happened when Tucker Carlson sicced a mob on her and the internet handed them everything they needed to make her life a living hell.

Groundhog Day: Can I buy you a drink?

Beau: The next clip here comes from Harold Ramis’ cult classic 1993 movie Groundhog Day.

Groundhog Day: “Sweet vermouth on the rocks with a twist, please.”

Groundhog Day: “The same. That’s my favorite drink.”

Groundhog Day: “Mine too.”

Beau: Phil Connors, that’s Bill Murray, doesn’t like sweet vermouth in this movie. But his producer Rita, AKA Andie MacDowell, she does. And he’s lying. He’s running the same day over and over, if you know the movie, watching her, memorizing her, refining his approach—until her behavior becomes predictable enough to him to get her to do what he wants. That’s not charm. That’s surveillance.

Groundhog Day: Maybe he’s not omnipotent. He’s just been around so long. He knows everything.

Beau: And that’s the internet. Not magic. Not fate. Just repetition, memory, and leverage. For more than twenty years now, the internet has been running the same day on us — actually, 1993 was when the World Wide Web became a public thing. You could use it. Now, what’s it been doing? It’s been learning our patterns, selling what it learns, calling that connection. Connection. Connection sounds so good. AI is now in the process of finishing the job, and we have to ask as it becomes so good at what it does: does knowing everything make life better… or just creepier, and a whole lot easier to control? I’m Beau Friedlander, and this is what the heck, the show that asks, in a world where your data is everywhere, how do you stay safe online? Virginia Heffernan, welcome. Virginia writes for the new Republican and has a SubStack called Magic and Loss. She wrote a book by the same title, Magic and Loss: The Internet as Art. Basically, she’s in the business of politics for English majors. That’s what she likes to say, which I think is super funny. Virginia. Welcome to the podcast.

Virginia: So wait, where are you right now?

Beau: So What The hack is now part of DeleteMe. Have you ever heard of DeleteMe?

Virginia: Are you kidding? And I’m so happy you’re wearing the shirt. DeleteMe came to my rescue after Tucker Carlson, who like got me in his sights and led a show with a picture of me, and then talked about how stupid I was naturally and, and sicced his many, many followers on me and other female journalists that he covered in the same week. And I was inundated with you know, threats and threats on my children in my actual mailbox written. Some of them were on thank you cards and one of them said thank you, and then inside, “for being such a bitch.”

Beau: Now this was actually in your physical mailbox?

Virginia: In my mailbox. So they had my address, I got calls on my phone, and just tons of hate mail through every email I’ve ever had.

Beau: Wow.

Virginia: Um, so we, I got the FBI involved and I got the cops, local cops involved, but no one, they can’t do anything to like, take your name off, making me less findable. I thought I was pretty unfindable. I was extremely findable. So DeleteMe really came to my rescue, and I’ve just been an evangelist for it ever since, because you don’t know how messed up your life gets until this administration and its many acolytes turn on you. And it was a pretty terrifying couple months. And it stopped pretty much the second I had DeleteMe involved. So that is a very heartfelt something I would’ve said to anyone, not just someone wearing a DeleteMe shirt.

Beau: Well, the funny thing is, I love my DeleteMe shirt. I feel like this makes me look like a nicely groomed Jerry Garcia. But we’re not gonna talk politics today. We’re gonna talk internet because you know a lot about that too.

Virginia: Yes.

Beau: We’re talking about the internet. We’re talking about Groundhog Day, and we’re talking about what’s broken that keeps us stuck in these loops. Now, this episode, I’ve been thinking about this since last fall when I went out to visit Seth Godin, and I was so excited that it was the first thing that I blurted out when we sat down: “Seth,” I was like, “The internet is Groundhog Day.” He didn’t miss a beat.

Seth: So it’s not that the internet is Bill Murray, it’s that there are companies that are rewarded for acting like Bill Murray.

Beau: Exactly, except Bill Murray’s got a name in the movie and it’s not Bill Murray. It’s Phil Connor. Listen to this.

Groundhog Day: I’m a God.

Groundhog Day: You’re a God.

Groundhog Day: I’m a God. I’m not the God.

Groundhog Day: You’re not a God. You can take my word for it. This is 12 years of Catholic school talking.

Beau: Okay, so if you haven’t seen Groundhog Day, and you should. It’s a classic by Harold Ramis. Here’s the setup: Bill Murray plays Phil Connors, this sort of narcissist weather man who goes out to Punxsutawney Pennsylvania to cover weather. Punxsutawney Phil, the groundhog sees his shadow. There’s a snowstorm, and he gets stuck, and the next morning he wakes up and it’s the same day. February 2nd again, and again, and again. Day after day after day after day. The clock, you remember it’s a digital clock, flipped over to 6:00 AM. Wakes up…

Groundhog Day: Okay campers, rise and shine! And don’t forget your booties…

Beau: At first, he doesn’t know what’s happening, and then he gets angry, and then he realizes, “Hold on. If I’m stuck in the same day forever, I can learn everything. I can watch people, memorize what they do, figure out exactly what they’re going to say before they say it,” and Phil Connors, well, he’s a jerk. So he uses it.

Groundhog Day: This is Doris, her brother-in-law Carl owns this diner. She’s worked here since she was 17. More than anything else in her life, she wants to see Paris before she dies.

Groundhog Day: Oh boy. What I…

Groundhog Day: What are you doing?

Groundhog Day: This is Debbie Kleiser and her fiance. Fred.

Groundhog Day: Do I know you?

Groundhog Day: They’re supposed to be getting married this afternoon, but Debbie is having second thoughts.

Groundhog Day: What?

Groundhog Day: Lovely ring.

Beau: Now, see, by this point in the movie, Phil Connors has lived this day so many times he’s basically memorized the entire town. Every person, every routine, every secret. He’s not a god. He’s just been stuck in the loop long enough to know everything about everyone, sort of like Meta or Google, and now he’s going to prove it.

Groundhog Day: This is Bill. He’s been a waiter for three years since he left Penn State and he had to get work. He likes the town. He paints toy soldiers and he’s gay.

Groundhog Day: I am.

Groundhog Day: This is Gus. He hates his life here. He wishes he stayed in the Navy.

Groundhog Day: But I could have retired on half pay after 20 years.

Groundhog Day: Excuse me. This is some kind of trick.

Groundhog Day: Well, maybe the real God uses tricks. You know, maybe he’s not omnipotent. He’s just been around for long. He knows everything.

Groundhog Day: Oh, okay. Well, who’s that?

Groundhog Day: This is Tom. He worked in the coal mine until they closed it down.

Groundhog Day: And her?

Groundhog Day: That’s Alice; came over here from Ireland when she was a baby. She lived in Erie most of her life.

Groundhog Day: He’s right.

Groundhog Day: And her?

Groundhog Day: Nancy. She works in the dress shop and makes noises like a chipmunk when she gets real excited.

Groundhog Day: Hey!

Groundhog Day: It’s true.

Groundhog Day: How do you know these people?

Groundhog Day: I told you I know everything. In about five seconds, a waiter’s gonna drop a tray of dishes. 5, 4, 3.

Groundhog Day: This is nuts.

Groundhog Day: 2, 1. [CLATTER]

Virginia: Wow, I’d forgotten that.

Beau: Can you see why when I was watching that I thought, “God, that’s the internet.”

Virginia: Yeah. The idea of the recurring day or the memory, I guess of the day no one else remembers is… I wouldn’t have connected it to surveillance online.

Beau: The surveillance economy. And the surveillance economy which includes data brokers. But this is the whole panoply of data brokers and data related companies and put Meta at the very top of that list. And Google and other social media companies where they are able to know who you know and who they know and who you’re related to and what’s happened in your life and what’s happened because your cousin once removed wrote a post about your great-great-great-great grandfather and there’s 23andMe. I could go on and on.

Virginia: Yeah.

Beau: So we’ll just call it the internet.

Virginia: Yep. What stands out also is just the state of the economy on the eastern seaboard and just the discussion of how the Penn State guy as a waiter and the waitress can’t go to Paris and there’s what the internet and what the Bill Murray character would know about you, that is, what makes up your identity are essentially small facts about your economic and familial situations where around the origin of social media, we didn’t really care if you were posting to Facebook about, well, your wedding didn’t happen because you’d had second thoughts about it. You just thought, why would some overlord, why would some all-seeing eye care about knowing what I had for breakfast and all the usual trivia that was Twitter and Facebook were expected to document? But now I think if we saw this again, you’d see a more diverse crowd in the diner and you would see great anxiety about people’s political positions online. Even their relationship, like the interior lives or the private lives of people look different now. Like, we almost cheat them out to the cameras. Like, what is supposed to constitute your identity?

Beau: I mean, so this is 1993, and what I found, the first thing that I found interesting was not that Clinton became president, NAFTA passed, the World Trade Center was bombed for the first time. Waco, Waco Texas. So all these things, 1993, cool. But you know what the most important thing is that happened in 1993? The World Wide Web became public. That’s when it happened.

CNN Clip: It spans the globe like a super highway. It is called “internet.” “The net” to longtime users. Internet is a whole group of networks. The net is made up of some 12,000 individual computer networks. Internet began back in 1969. It was a tool of the Pentagon. But nowadays, just about anyone with a computer and a modem can join in…

Virginia: Wow.

Beau: So this is pre-computer, this is like a pre-computer allegory about our lives online.

Virginia: There are actually archeologists, who do work on basically, I think it’s called like pre-digitizing societies. So they are even Greek and Roman examples of small communities that are acting digitally avant la lettre, or like before there is actual digital life. Sorry, but…

Beau: Avant la lettre means before the writing.

Virginia: Perfect. Before the letter of the internet. I gotta say there’s no better application of avant la lettre than that. So if you, if we want to like, if we’re ever gonna indulge in that kind of ridiculous pretension, now’s the time. But anyway, yes. Self digitizing or pre-digital, but sort of anticipating digitization, that seems like what you’re describing is going on in the movie. I’m trying to see if I agree with you though.

Beau: Stay with me. We’ll be right back after this. Here we go.

Virginia: Let’s hear it.

Groundhog Day: Hey, did you see the groundhog this morning?

Groundhog Day: Uh-huh. I never miss it.

Groundhog Day: What’s your name?

Groundhog Day: Nancy Taylor. And you are?

Beau: He’s already struck out with her several times.

Virginia: Okay.

Groundhog Day: What high school did you go to?

Groundhog Day: Lincoln. In Pittsburgh.

Beau: She won’t give him the time of day, but obviously he gets another try every day because the day keeps repeating.

Groundhog Day: Who are you?

Groundhog Day: Who was your 12th grade English teacher?

Groundhog Day: Are you kidding?

Beau: So today he’s just decided to be a jerk and shake her down for information.

Groundhog Day: No, no, no. In 12th grade, your English teacher was…

Groundhog Day: Mrs. Walsh.

Groundhog Day: Mrs. Walsh. Yeah. Nancy. Lincoln. Walsh. Okay. Thanks very much.

Groundhog Day: Hey. Hey!

Beau: So what just happened there was in, you know, one of the things that just happened there is like, that’s how cyber criminals work, right?

Groundhog Day: Nancy? Nancy Taylor! Lincoln High School. I sat next to her in Mrs. Washer’s English class.

Groundhog Day: Oh, I’m sorry,

Groundhog Day: Phil Connors.

Groundhog Day: Wow, that’s amazing.

Groundhog Day: You don’t remember me, do you?

Groundhog Day: Um.

Groundhog Day: I even asked you to the prom.

Groundhog Day: Phil Connors.

Groundhog Day: I was short and I’ve sprouted.

Beau: They’re just trying to get enough information about you in order to pull a scam on you.

Groundhog Day: Gosh, how are you?

Groundhog Day: Great. You look terrific. You look very, very terrific. But maybe later we could…

Groundhog Day: Yeah, whatever.

Virginia: I’m wondering about the, like the spearfishing or the sort of inquiry about what, where she went to high school and who her teacher, what her teacher’s name was. Also just the willingness, the sort of sociological willingness to give up, answer questions that are asked you on the street. The fact that even she who’s trying to brush him off is willing to give up the name of her high school is actually also really interesting, that other people’s curiosity about you is, it’s flattering and we’re all walking around. I don’t know if I’ve ever told you this, but I wrote once about this, that was I guess phished, catfished by, um, Larry Summers.

Beau: No.

Virginia: Yes. Okay.

CBS Clip: Former Harvard President Lawrence Summers will take a break from teaching at the prestigious university after his continued relationship with Epstein was exposed.

Virginia: Larry Summers’ real account on Twitter dmd me on Twitter, so it was his real verified account, dmd me and said, “Hey, I really like your work and I wonder if you’d look over something I wrote.” Now obviously the former treasury secretary and president of Harvard is not gonna ask my opinion of something that he wrote.

Beau: No. No, that’s not true. That’s not true. If he’s read your op-eds and stuff, I disagree. He might. That’s actually plausible.

Virginia: Well, okay. Apparently, by the way, apparently I’ve just been waiting my whole life to be of service to the former treasury secretary because yes, I clicked. I clicked and my whole screen was filled with Turkish letters, all of it. Um, and this guy came up, this picture of this like AI kind of warrior came up saying like, we’ve seized your whole account. And suddenly they were like, running my Twitter account. And anyway, it was a huge headache. But the point is, somebody is sort of like… inquiry, even as that woman in Groundhog Day is trying to blow off Bill Murray, she can’t help it. She starts giving up information about herself. She just is cracked open, you know? It’s very hard to gray rock and just say no to these things.

Beau: You know what? You know why? Here’s why. I don’t know why, but I’m gonna say my theory. Connection. So, one of the reasons I think Facebook worked was it promised connection. It promised, “You know all these people you used to know? You’re gonna know ’em again. They’re on here. All you gotta do is hit ‘friend’ and you can meet ‘em again. Kindergarten, right back in your life.” So that connection happens on the street too. And when I was on a train from DC not that long ago, and I was sitting next to someone who’s clearly a journalist and really wanted the whole car to know was, was going through edits in the train, super annoying. And I was writing something and, she finally, she said something so wrong that I said, I don’t know why I offered it, but I was just like, you know, “I heard. You know, that edit might get you in trouble.” And she was like, “Are you a journalist?” And I said, “I’m sorry, I shouldn’t have said anything.” And then I said, “I gotta work.” And I went back to work not answering her question. She circled back. “Where do you write? I said, “On my computer mostly. I really do have to work.” And she kept trying and she finally said, “I have to get off the train, but I’m pretty sure that you do national security journalism.” And I was like, “Cool. Have a great day. Good luck with your article.” And that is all I will give, because if I want to connect, I’ll call you up. If I wanna connect with a journalist or intellectual or writer or reader, I’ll call those people who I want to hear from and who I wanna share my thoughts with. I never was big on Twitter, so yeah, I do think it’s opt-in, but what we’re opting in for is connection, and I think that brings us to our next clip, which is really alarming when you think about the fact that what we’re really looking for, the comfort of being known, is very alluring.

Groundhog Day: So what are the chances of getting out today?

Groundhog Day: The van still won’t start. Larry’s working on it.

Groundhog Day: Wouldn’t you know it? Can I buy you a drink?

Beau: She’s already is totally annoyed by him. She’s his producer. He’s a total arrogant jerk.

Groundhog Day: Okay.

Groundhog Day: Jim Beam. Ice. Water.

Beau: So he’s struck out with her a million times.

Groundhog Day: For you, miss.

Groundhog Day: Sweet vermouth in the rocks with a twist please.

Beau: Now here’s Phil Connors doing what he already knows will work because it worked with a woman who went to high school in Pittsburgh and coughed up the name of her teacher and other stuff that helped him get a date with her. So he exists now to do reconnaissance. It’s okay if he strikes out. Every wrong answer will lead to a right one. He’s the embodiment of a selfish algorithm. The clock rolls around to 6:00 AM again, he tries to get in her good graces again, and yeah, that’s a euphemism.

Groundhog Day: What are the chances of getting out of town today?

Groundhog Day: The van still won’t start. Larry’s working on it.

Groundhog Day: Oh, wouldn’t you know it? Can I buy you a drink?

Groundhog Day: Okay.

Groundhog Day: Uh, sweet vermouth, rocks with a twist, please.

Groundhog Day: For you miss?

Groundhog Day: The same. That’s my favorite drink.

Groundhog Day: Mine too. It always makes me think of Rome, the way the sun hits the buildings in the afternoon.

Groundhog Day: Well, what should we drink to?

Beau: Now he’s taking another try at making her like him.

Groundhog Day: I like to say a prayer and drink to world peace.

Groundhog Day: To world peace.

Groundhog Day: World peace.

Beau: So next, they are post-bar, hotel -bound, and Phil Connors busts a move. They kiss, but just enough for Rita Hanson, played by Andie MacDowell, to push him away and remember herself–remember who she actually is. Not who the internet is reflecting back to her or trying to gently guide her to be.

Groundhog Day: Oh no. I can’t believe I fell for this. This whole day has just been one long setup.

Groundhog Day: No, it hasn’t.

Groundhog Day: And I hate fudge. Yuck.

Groundhog Day: No white chocolate, no fudge.

Groundhog Day: What are you doing? Are you making some kind of list or something?

Groundhog Day: No.

Groundhog Day: Did you call up my friends and ask them what I like and what I don’t like?

Beau: No white chocolate, no fudge. He sounds like an LLM calling out its own drift, and thus failure to execute whatever was asked.

Virginia: If he is a kind of proto internet, is he optimized for some kind of particularly barbaric aggression? And it actually…

Beau: Yes.

Virginia: Okay. Okay. Tell me more. Tell me why you think that. What, why isn’t this just, you and I go on a date and I call up a bunch of friends of yours and say, “What’s Beau into?” You know?

Beau: Yeah, that’s great. No, that would work. But that would work. And that’s not what’s happening here.

Virginia: Okay. Tell me.

Beau: First of all, if we just take the scene at face value, this is a narcissist who has weaponized what he knows to get what he wants.

Virginia: Mm-hmm.

Beau: I think. I think that he’s gathered this information ’cause he has a theory that mirroring the person is going to get him where he wants to go, but it feels very transactional and planned.

Virginia: I mean, don’t you amplify the things that you’re interested in, points of commonality and play down the other ones? And also, doesn’t he like her?

Beau: Yeah, but not if it’s just in the service of… He.. I don’t know. I think ’cause he’s been, he has been a swordsman in the movie. He has bedded a few people. What I was thinking in this scene was that he’s doing… He’s kind of Meta’s, “privacy is dead,” Google “don’t be creepy” in incarnate.

Virginia: Mm-hmm.

Beau: And why? It’s very simple. This is why I said yes so confidently, ’cause they’re selling stuff. Because if I know those things about you because I watched you like stuff with your friends from high school on Facebook, I can sell you stuff.

Virginia: And he’s also, right, pretending they have something in common that they don’t actually. Later she’ll find out he doesn’t care at all about Rome, which is like, seems like the sort of typical route to divorce, which is like, “You pretended you were into UFC fighting in the beginning and now you haven’t wanted to go with me for 10 years.”

Beau: Sounds like a bad date.

Virginia: Actually, I did pretend to be into UFC fighting to like court, my husband.

Beau: So again, I’m thinking of it as an allegory. Bill Murray is not a narcissist who’s maybe being chivalric and trying to get a girl that way. He’s the internet, and he’s plowing through everything the way the internet does, which is it gathers information and then it deploys it, and that deployment of information has become more and more subtle and smart. Like, you mentioned getting catfished or spearphished actually by Larry Sumners. The idea that the way in can be super interesting. Later on in the movie, where this process of Bill Murray as the internet, the whole internet, is learning stuff and taking that data and deploying it and building it, it defeats…that process actually destroys the narcissism that drove it in the first place. And that’s what’s interesting.

Virginia: That’s good.

Beau: Because it comes out the other end. And we’re gonna look at this. So that process destroyed the narcissism that drove it in the first place and it turns into something resembling AI.

Groundhog Day: Yeah, I was just talking with Buster Green. He’s the head groundhog honcho, and he said If we set up over here, we might get a better shot. What do you think?

Groundhog Day: Sounds good.

Groundhog Day: Larry, what do you think?

Groundhog Day: Yeah, let’s go for it.

Groundhog Day: Good work, Phil.

Beau: ChatGPT knows that you should probably ask the producer and the cameraman to get the best possible result.

Virginia: Yeah, that’s amazing.

Beau: That is that surplus of empathy turned into AI.

Virginia: Sycophancy, right? The shortcoming of the ChatGPT sycophancy.

Beau: Yeah, exactly. And here’s what worries me about that sycophancy—it’s not just that AI learned to be nice. It’s that it learned to be nice because being nice gets us to stay longer on the LLM, click more, buy more. Well, the LLMs are just starting to advertise, but just be there more. What do you do with all that information at the end of the day, right, but be helpful? Sure. But helpful to whom? To us? Or to the people selling stuff to us? So in business, this whole motion that we’re talking about is marketing. He can do anything he wants. He could make the world a better place because he knows all this stuff.

Virginia: Yeah. Interesting.

Beau: At some point the shopkeeper says how can I help you, and they mean it. They mean it because they want to sell you something, but they’re also successful because they’re genuinely helpful.

Virginia: Yeah, I think that that’s right. And I like that you are seeing that marketing and sales and trade are like what some people call the double thank you. Like ideally everyone’s getting something out of it, and it’s not just a one way act of barbarism. And it seems like now we have a world where Andie MacDowell and Bill Murray seem to be mutually benefiting from their relationship. And we might also, in human terms, call that love. And also there’s just so much fun around it. You know? That’s I think why it’s Bill Murray, right? There’s some inefficiencies in it, in his game, that are his charm. Now what I wanna ask is in that last scene where we see them on the shoot and they’re making decisions about how to do it, is he coming up? Is he just building consensus by asking both the producer and this other figure what they should do to make everyone feel good and like advance his ends? Or is he making the shoot somehow better or more efficient or better work done in the world?

Beau: Well, you said this just now.

Virginia: Okay.

Beau: It’s a thank you, thank you.

Virginia: It is. Okay.

Beau: Why you will hear people say, “Instagram is listening to me, but I don’t mind because I just found the perfect grill.”

Virginia: Mm-hmm. Right.

Beau: The “thank you, thank you” really matters here. The problem is that the “thank you, thank you,” all that information, it doesn’t get me the perfect grill. It doesn’t get me anything. It makes data brokers richer though. That’s how you got notes in your mailbox. Because of that excess, because of data brokers taking things they didn’t need and putting them places where it shouldn’t be.

Virginia: I think that’s right. I mean, what happens with all the three players in the last scene? I probably should know it.

Beau: No.

Virginia: I mean the last one you showed me. Is everyone mutually satisfied? What are they agreeing on?

Beau: Everyone’s shocked. Everyone’s shocked, including Bill Murray.

Virginia: Because he’s just being nice. But is he getting anything?

Beau: He’s being thoughtful, yeah.

Virginia: He’s better at his job. He’s making like the shoot go better .

Beau: No, the cycle breaks. It’s over. He gets, that’s what sets him free. That is the kiss. That is the kiss that makes the frog a prince or princess.

Virginia: Yeah. I see, I see. At some point, he jumps the tracks of these even exchanges.

Beau: Yeah. Well, and they keep saying like, “We’re gonna keep you in this, you’re gonna be in this rut,” literally to say, keep with your metaphor, “until you understand.” Like Aimee Mann said, it’s not gonna stop till you wise up. You’re going to have to eventually understand that you are the problem and only you can be the solution.

Virginia: So you say that, so that last scene that you showed me is…all I wanna know is, are they making the shoot go better or is any money involved?

Beau: Yeah. There’s money involved in that everybody has done their job better, which usually results in promotions.

Virginia: Okay. So, right. I mean, ’cause humans are sort of like seduced by niceness and that means that they work better and he’s catching more flies with honey and he’s…

Beau: And it’s “thank you, thank you.” Yeah.

Virginia: He’s a better manager now. And maybe the local advert lumber camp company or advertiser on the local news show or whatever is gonna like attract more eyes and pay more for the slot on the show, and there is some way you can imagine it being monetized, but it’s very incomplete, you know. It’s very unclear whether the surplus of niceness that counts as being human is like, maybe the whole thing is surplus at that point. You know?

Beau: It results in… You asked about this value question, so let’s look at the final one.

Groundhog Day: Hello. Welcome to our party.

Groundhog Day: Phil. I didn’t know you could play like that.

Groundhog Day: Oh, I’m versatile.

Beau: They’re at an auction.

Groundhog Day: What is that all about?

Groundhog Day: I really don’t know. They’ve been hitting on me all night.

Beau: They’re at… what do you call it when you auction dudes off for dates for charity? They’re at one of those things.

Virginia: Oh yeah.

Groundhog Day: Okay, folks. Attention. Time for the big bachelor auction. Phil Connors, come on up here.

Groundhog Day: Alright, now what am I bid for this fine specimen?

Groundhog Day: $5.

Groundhog Day: The bidding has begun at $5.

Groundhog Day: $10. 15. 20. 25. 30. 35. 40. 45. 50. 55. 60.

Groundhog Day: I did 60. Do I hear more?

Groundhog Day: $339 and 88 cents.

Beau: So, you know, my sense there is that like, and there is your monthly LLM subscription. You know, you just got to the point where you’re like, Uh-huh, I will pay for this.

Virginia: And that’s a human face. Yeah. So something I’ve… this is ‘93, but one of the dates that I get in my head is 1969, the year of my birth.

Beau: Mine too. Yeah. Oh, wait, we shouldn’t have shared that. That’s, that’s personal information, but what I’m thinking, people can find it

Virginia: I think, right. I think that that would be easy enough to find. And I’ve certainly written it, but that is the first year they offered the Nobel Prize in economics which had previously been reserved for only hard sciences. And it’s a social science that jumped from being just competing theories the same way psychology and sociology and anthropology is, that was like one other way to explain how people live, to suddenly having these laws. And one of the laws that we are like very (and “laws,” right? Because none of them are natural laws) that we are very in the spell of, is the idea that we are all at heart consumers or shoppers, right? Rather than like producers, or artists or, you know, or like people caught in Freudian neuroses. That that’s like a fundamental driver of our identity is that we’re consumers. And I’ve written marketing stuff before and the only way you describe people is as consumers or customers. It’s bananas. But I think that economics is one social science and the other ones compete very well with it. And I think the.. I suspect that this century is gonna be a century much more interested in philosophy than economics. And that’s maybe a longer argument, but the idea that we’re fundamentally shoppers, I think the internet gets us wrong when it thinks that about us. You know, when I was thinking it can sell data to a company that can sell me a barbecue grill or might wanna sell me a barbecue grill, I mean, talk about inefficient. Mostly I use TikTok, but I never get to the cash register. I’m not much of a shopper. There’s like, the problem with your and my and many people’s kind of social identity is that it’s hard to predict exactly what demographic we’re in. Like what are we gonna buy, like fancy things, or Uniqlo or nothing, or thrift? Are we gonna have BMWs or no cars or whatever? And even a ton of data gouging around, you know, our dates at birth or who we date or whatever, does not do very well in predicting what we’re gonna buy. And the other thing is I guess to be especially cynical about data, you have to just think, “Well, the internet sees me because they see my shopping habits.” I mean, we haven’t talked about our political identities, or that all that I am are the bits of data that could be used to seduce me by Bill Murray or all that I am are bits of things that could make me optimized to make the TV station work better. Right? The like, who, whom? Lenin’s who, whom, like, who’s doing this to whom is like what marketer is doing this to what poor chump? And all we in the equation are not even objects of violence. So I don’t wanna, you know, say we’re all great artists, but that we’re seen either as potential deportable people, right? Like any data Palantir is collecting is probably less interested in the fact that I buy a lot of perfume, and so because my identity is somewhat constructed in the mirror of what is wanted out of me, what data is wanted out of me, I then like wanna elude that kind of data, or giving up that much data about myself. And then I start to become a kind of different player in the Matrix and they move their thing and become a different player. And all the while we all know very clearly that so much of us doesn’t show up online. Like when I was writing on my tour for Magic and Loss, someone said, “You know, I just don’t see this kind of self-invention going on online, anytime that someone could like hack your… could take everything from you and hack your… really get into who you are and hack your Citibank account and empty it out.” And I was like, “But is it possible that I’m not the number in my Citibank account? Like it would be terrible to lose the $15,000 I have in my savings account on Citibank, but would that do damage to the thing I ultimately am?” And if we’ve gotten that far, that Homo Femo Economicus is like the, the be all, end all of who we are… we’re not physical agents, we’re not political agents. We’re not artists. We’re not thinking weird thoughts. We’re not psychologically crabbed strange people. We’re not people who act sociologically. We just are consumers. And if they wanna see us as consumers, because that’s a way to maximize whatever, more power to them. But talk about inefficient. Like, all I feel like I’m doing is eluding the vision of me as a whatever.

Beau: Do you understand what I was seeing when I looked at Groundhog Day? I was like, wow, this is some sort of cultural marker for something it wasn’t at all talking about. Obviously. It’s W.K. Wimsatt’s intentional fallacy in full action.

Virginia: Do you think now because… I don’t know, because pop culture speaks to us and it… I think something like this could be prophetic. And I love the idea, by the way, of romantic comedy is doing better than science fiction. This is exactly how pop culture does work. You know,

Beau: Good. All right.

Virginia: I’m obsessing about this Mussolini movie. I don’t know if you saw it, but the Joe Wright movie, it’s so good.

Beau: No, I didn’t.

Virginia: In it he keeps saying, “I’m an animal. I smell the future.” And it’s just like that fascist obsession with what the future is is really interesting. And I can imagine, I mean, why did this land in our cells this way? And there were kind of proto internet stuff circulating. There were zines, there were like, I don’t know. There was a lot.

Beau: It was the year the internet started. Yeah.

Virginia: There were a lot of consumer culture. There was a lot of other things, and a movie like this catches on, changes the entire meaning of Groundhog Day, by the way. It only means one thing now and it’s this movie and then, and gets in our heads and has explanatory power for us over time, and also is so like, you know the future when you see it and usually you’re laughing because it just lands. It expresses something important. So I think you’re absolutely right. And also movies are so made by such groups of people that I don’t think you have to say that there’s some auteur there. And really auteuristic movies also don’t predict the future, because it’s just like one guy in his own head. But anyway, I think you’re absolutely right and I don’t wanna overlook the fact that you dropped a huge thesis bomb at the beginning and like saw it all the way through. Because that is really impressive. I wish people did that all the way. I wish people did that more And did it flamboyantly like you just did.

Beau: Well, it’s data removal for English majors.

Virginia: Data removal for English majors. Exactly. And like, and pop culture. Those are the places to look.

Beau: Yeah. Virginia Heffernan, author of the book Magic and Loss: The Internet as Art, and her active substack, called also Magic and Loss. There’s a link in the show description. So what just happened? Phil Connors breaks the loop by stopping the con. He quits treating knowledge as leverage and asks a different question: What if I actually helped? What if I actually got into the “thank you, thank you”? The internet hasn’t asked that question yet. Maybe AI is starting to, but LLMs also just started to advertise, so maybe not. Ancient merchants learned about customers so they could sell them wheelbarrows, and eventually that curiosity became care, as it would, I guess. The internet went the other direction. It learned about us to own us. Phil Connors escaped Groundhog Day by understanding that knowledge without care is just another way to run a scam. Maybe that’s our way out too. Is the scam all the data out there that’s associated with me and about me? I think yeah, I do, and that’s why I try to keep as little as I can out there on the internet. So with that in mind, now it’s time for the Tinfoil Swan, our paranoid takeaway to keep you safe on and offline. Are you using an LLM? And if so, how good is your security? How good is your privacy practice? What are you putting in there? Let’s talk about it. Here’s what you need to know: most AI chatbots—ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini—They’re training on your conversations by default. That means that when you open the box of this particular product, it starts to take things from you by default. It means everything you type could end up teaching the next version of the model. Your ideas. Your drafts. Your strategies could get coughed up in someone else’s query. First rule: check your privacy settings. In ChatGPT, turn off chat history and training. In Claude, look for data retention controls. Look for the incognito, because you can also say “Don’t train on my content” there. Google’s Gemini has similar options. These settings do exist, but if an LLM were a person, this is not something that’s tattooed on their knuckles or their forehead. You’ve got to go looking for them, and when you do, flip them to the right setting. Second: Never put sensitive information in a chatbot. Okay? I know you’re writing the next great novel and you’re putting it on there. Don’t do it, because it’s anybody’s novel now. No passwords, no proprietary code, no confidential client data for sure, no unpublished work if you care about protecting. Now, is it really going to go walk about? I don’t know, and that’s why you need to be careful. If you wouldn’t post it publicly, rule of thumb: don’t put it in an LLM. Third: Use incognito. Use it, or a temporary chat mode. It’ll be something different depending on what LLM you’re in. Now, they’re designed to delete your conversations after the session ends. You can also just delete chats when you’re done. Most LLMs after 30 days, it’s out anyway. It’s gone. They’re not storing everything. Or are they? We don’t know. Again, be careful about what you post. Now fourth: read the terms of service and privacy policy. And yeah, I know, nobody does—but listen. There’s a trick now, and it’s funny, because it’s the LLM itself. Ask it to summarize what they’re collecting and how they’re using it. And you can even ask the LLM to give you the questions to ask it to protect whatever it is you’re trying to protect, and remember finally that companies change their policies. So what might have been true last year may not be true now, so any assumptions you’re making about your content that you’re putting on these LLMs, bear in mind, if it’s something really sensitive, check today. Check the day of and see what’s going on because policies change. Now, what’s private today, we’ve learned this a long time ago, not private today. Tomorrow, no idea. The internet learned how to own us a long time ago, right? Now, you can get some agency back. You don’t need to be owned by the internet. It’s hard, but you can start reducing the ways in which you are known to the internet, and DeleteMe’s a perfect way to start, but here’s the deal. In the same way the internet did what it did, AI can to, so don’t hand AI the same playbook. Be careful. If you’re using an AI chatbot, just remember, set the privacy setting super tight. Make it forget what you’re doing. Don’t let it train on your data, and don’t put anything on there that you don’t want people to see, because breaches happen and you don’t want your stuff to be wrapped up in that. Okay. Stay safe out there. We’ll talk to you next week. Thanks for listening. Bye-bye. What the Hack is produced by Beau Friedlander (that’s me), and Andrew Steven, who also edits the show. What the Hack is brought to you by DeleteMe. DeleteMe makes it quick and easy and safe to remove your personal data online and was recently named the #1 pick by New York Times’ Wirecutter for personal information removal. You can learn more about DeleteMe if you go to joindeleteme.com/wth. That’s joindeleteme.com/wth. And if you sign up there on that landing page, you will get a 20% discount. I kid you not. A 20% discount, so yes, color me phishing, but it’s worth it.

Learn More:

- Learn more about data brokers and how they contribute to a surveillance economy

- Learn how to keep your information safe so you can be a tougher target for scammers

- Discover more from What the Hack

Our privacy advisors:

- Continuously find and remove your sensitive data online

- Stop companies from selling your data – all year long

- Have removed 35M+ records

of personal data from the web

news?

Exclusive Listener Offer

What The Hack brings you the stories and insights about digital privacy. DeleteMe is our premium privacy service that removes you from more than 750 data brokers like Whitepages, Spokeo, BeenVerified, plus many more.

As a WTH listener, get an exclusive 20% off any plan with code: WTH.