Open Data, Hidden Risk: Employee Data & Cyber Threats + Prevention Tips

DeleteMe

Reading time: 11 minutes

Table of Contents

Firewalls, sandboxing, email filtering, you name it. Your organization can have the best security controls in place and still get hacked. How? Via your employees, specifically through malicious use of their personal information.

Cybercriminals don’t need access to the dark web or advanced tools to infiltrate corporate systems. A lot of the time, a well-crafted spear phishing email will do the trick. And when it doesn’t, there are plenty of other ways to exploit an attack vector that is extremely difficult to secure: humans.

Worst of all, the data that cybercriminals need to exploit employees isn’t hard to find. In fact, it’s publicly accessible on the open web. All a threat actor needs to do is perform open-source intelligence (OSINT).

Here are some OSINT sources threat actors use and examples of how they use them. We also show real-world examples of OSINT actions and the steps you can take for breach prevention.

Publicly Available Data Sources

The first thing to understand is where attackers get the employee information they need for OSINT.

There’s no shortage of OSINT sources threat actors can use to find all the data they need to manipulate employees and gain access to your systems.

To quote the ethical hacker Rachel Tobac, with whom DeleteMe’s CEO Rob Shavell spoke in a recent webinar, “I’m able to find new things almost every day for people that are asking me to do this OSINT, this open-source intelligence on them. And people will often think, “Oh, is this like dark web stuff we’re talking about?” No. It’s just the clearnet, regular internet that you and I are all using.”

Watch the full webinar, where Rachel and Rob discuss the role of personal data in social engineering attacks. Or, read our blog post summarizing some of the key points from the webinar.

Here are some of the most common OSINT sources:

- Employer websites. Company websites are a great source of executive personal information, including corporate email addresses and professional social media pages.

- Social media sites. Whether personal or professional, social networking accounts can provide threat actors with a ton of data, including education, work history, professional connections, interests and hobbies, upcoming trips, and family and friend information.

- Public records. Public record data can include marriage licenses, voter registrations, bankruptcy records, arrest records, and more.

- Crowdfunding platforms. Platforms like GoFundMe can give criminals an indication of causes an employee is interested in and can appear on search engine results pages for an employee’s name.

- Forums. Depending on how privacy-focused they are, employees may inadvertently expose their identities when participating in forums like Reddit or Quora.

- Public gift wish lists. Public wish lists on sites like Amazon, Crate and Barrel, Etsy, and others can make it easier for threat actors to figure out what brands to impersonate to get employees to click on malicious links or share sensitive details.

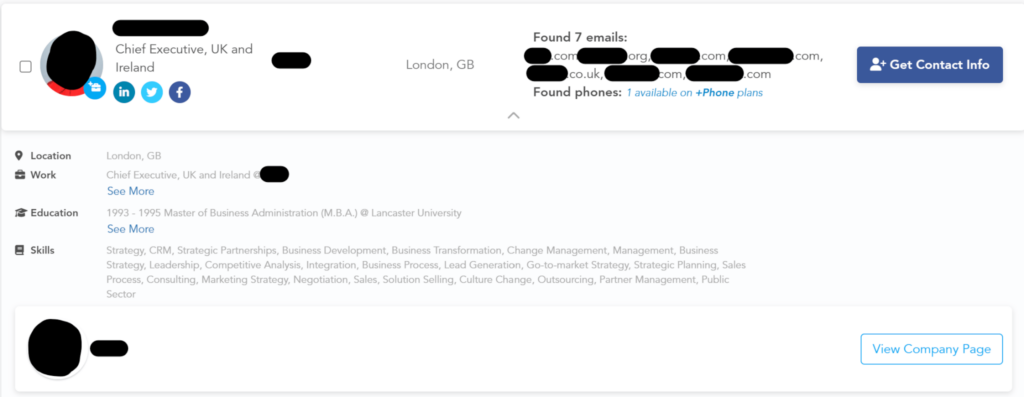

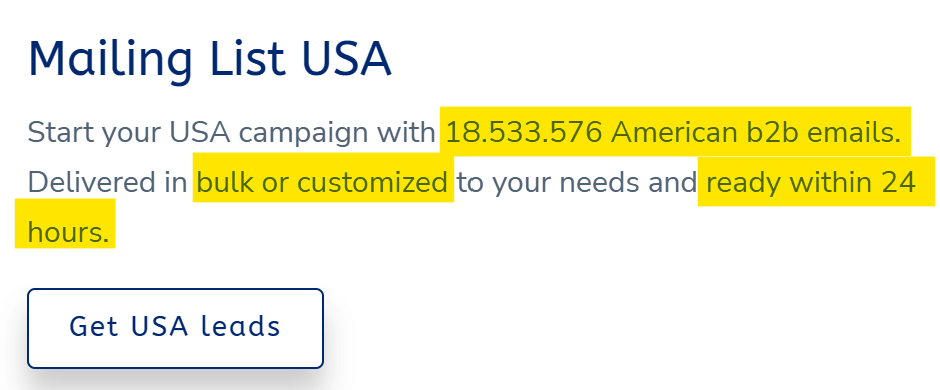

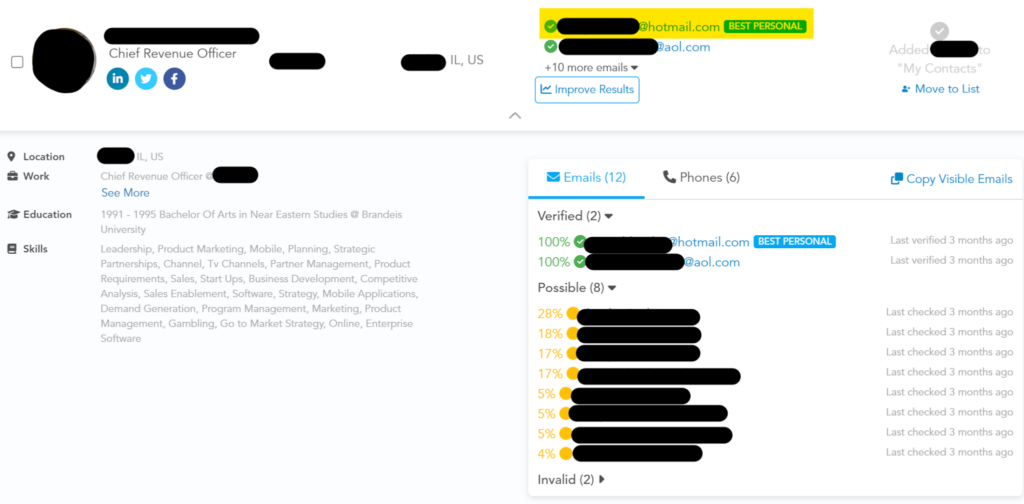

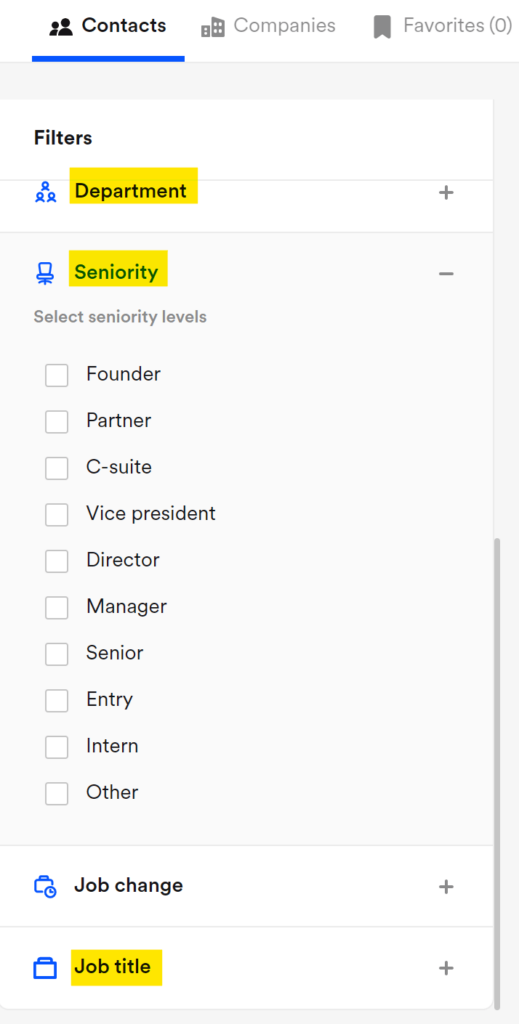

- B2B data brokers. B2B data brokers gather information from a variety of sources, compiling a person’s professional information in one place. These data brokers can also include org charts, affiliations and memberships, and employee quotes from press releases.

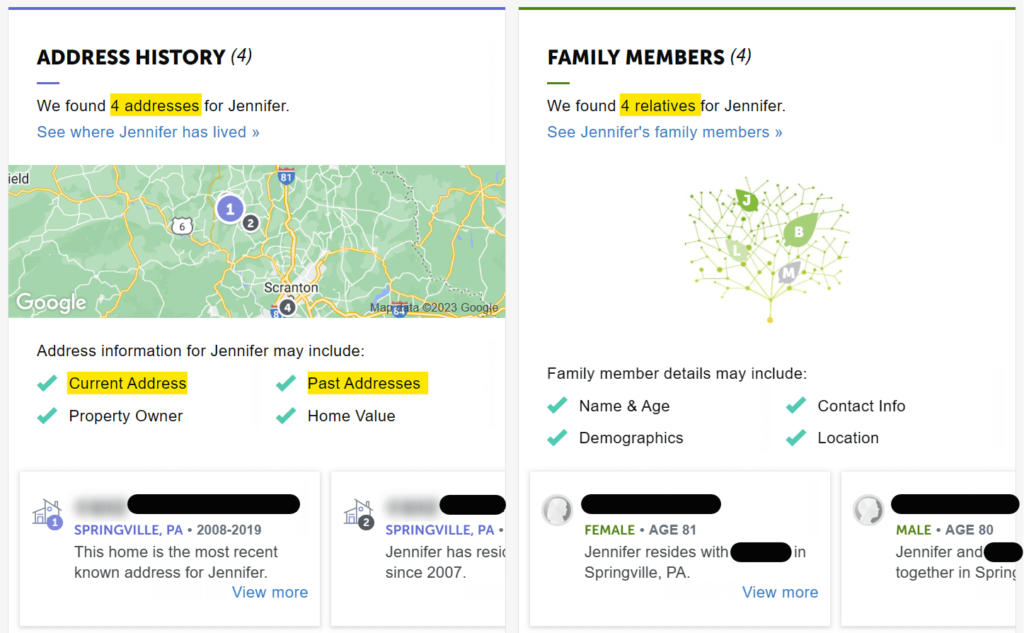

People search sites. Whereas B2B data brokers focus on professional data, people search sites include more personal information, like details on a person’s family, address history, and links to personal social media accounts.

How Threat Actors Use Publicly Available Employee Data + Real-World Examples

Below are some of the ways cybercriminals use publicly available data sources to compromise corporate systems.

Social Engineering

Social engineering is one of cybercriminals’ favorite tactics for conning employees into taking fraudulent actions like downloading malware, sharing sensitive information, and authorizing wire transfers.

Below are some of the more popular social engineering techniques.

Phishing emails

Mass phishing emails haven’t gone away. Threat actors still use large email lists to mass phish individuals and employees across numerous organizations and sectors.

Both personal and professional emails are valuable. For example, because many people reuse passwords, an employee who clicks on a phishing scam in their personal inbox and shares login details for a personal account may inadvertently expose their corporate credentials.

Information needed: Employee email addresses (personal or professional).

OSINT available: Employer websites, B2B data brokers, and people search sites.

Real-world example:

Last year, a phishing scam that looked like it came from Amazon harvested individuals’ and companies’ credit card details and phone numbers.

Spear phishing emails

Spear phishing attacks are more targeted than your typical phishing scam. Threat actors need specific email addresses, names, job titles, and other personal information to spear phish someone.

Learn more: How cybercriminals use data brokers for executive phishing

Threat actors will use someone’s personal and professional email addresses for this purpose. Some cybercriminal groups even favor personal accounts as a way to circumvent security controls on corporate networks.

Information needed: Employee email addresses (personal or professional), plus other personal information, like their hobbies, affiliations, family members, etc.

OSINT available: Employer websites, social media sites like LinkedIn, Facebook, and Pinterest, crowdfunding platforms, forums, public gift wish lists, B2B data brokers, and people search sites.

Real-world examples:

- In 2022, Chinese hackers targeted the personal Gmail accounts of government employees rather than their professional email addresses.

- A Belgian MP’s personal email was targeted with a spear phishing attack from a non-existent news organization saying they could provide information on human rights abuses in China. This was following his public resolution to spread the word of alleged government abuses in China.

- Earlier this year, scammers went after Microsoft Office 365 email accounts with a DocuSign scam.

Whaling

Also known as “CEO fraud” and “business email compromise,” whaling attacks are spear-phishing campaigns that target high-ranking employees. Members of the C-suite or individuals with access to data and funds, like the financial staff, are attractive targets.

One of the more important pieces of information threat actors look for when preparing for a whaling attack is a company’s org chart, which can be found on business data broker sites.

Information needed: Executive email addresses (personal or professional), the company’s org chart, plus other personal information, like the executive’s hobbies, affiliations, family members, etc.

OSINT available: Employer websites, social media sites like LinkedIn, Facebook, and Pinterest, crowdfunding platforms, forums, public gift wish lists, B2B data brokers, and people search sites.

Real-world example:

Several years back, cybercriminals scammed an agriculture company out of $17 million after sending its controller targeted emails that impersonated the company’s CEO.

What made these emails particularly believable was that they referenced the target company’s accounting firm and asked the controller to contact it for wire instructions. The criminals even included a (fake) phone number for an actual employee within the accounting firm and had someone impersonate them.

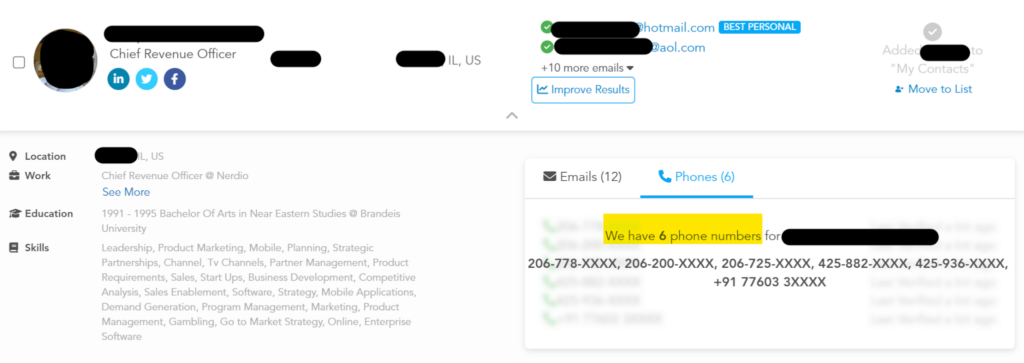

Smishing

SMS phishing, aka “smishing,” attacks happen through mobile phones and, more specifically, via text messages. They are often used to bypass 2FA systems that rely on text message prompts.

Information needed: Employee phone numbers.

OSINT available: Employer websites, social media, B2B data brokers, and people search sites.

Real-world examples:

- The Uber hack of 2022 was carried out by an 18-year-old who gained access to Uber’s systems by texting the company’s corporate information technology person and convincing them to send them their password.

- Last year, Cloudflare employees received phishing texts on their work and personal phones. Employee family members were also targeted.

- The Cloudflare scam was part of a larger campaign known as “0ktapus” that affected more than 100 organizations and involved MFA bypass attacks where attackers tricked victims into sharing credentials and MFA codes via a fraudulent Okta authentication page. Analysis of the attack revealed that the threat group first made curated lists of employers, employees, and phone numbers.

Vishing

Like smishing, vishing happens over the phone. However, instead of text messages, it involves hackers calling employees or leaving voicemails rather than sending fraudulent texts.

Information needed: Employee phone numbers.

OSINT available: Employer websites, social media, B2B data brokers, and people search sites.

Real-world example:

The Twitter hack from a few years ago, which resulted in criminals taking over celebrity accounts, is widely attributed to vishing. It is believed that threat actors found Twitter staff phone numbers and convinced them to share their usernames and passwords.

Insider threats

Insider threats come from individuals with legitimate access to an organization, including employees, contractors, partners, and third-party vendors. Insiders often misuse that access, whether maliciously or accidentally, and create security risks.

Information needed: Employee email addresses, phone numbers, social media handles, and other personal information.

OSINT available: Employer websites, social media, B2B data brokers, and people search sites.

Real-world examples:

- Ransomware groups have been known to email employees directly, asking them to help facilitate attacks and promising a portion of any ransom paid by the employer.

- Some cybercriminal groups offer to pay employees/business partners/suppliers at target companies for access to login details or for MFA approval.

- In one instance, a threat actor connected with an employee on LinkedIn and, under the pretext of a job offer, conned them into sharing confidential documents and clicking on a malware-infected link.

Credential stuffing

The classic example of credential stuffing is brute forcing someone’s login details until something eventually works, but not all credential-stuffing attacks are “dumb.”

Learn more: 3 ways data brokers enable corporate account takeover

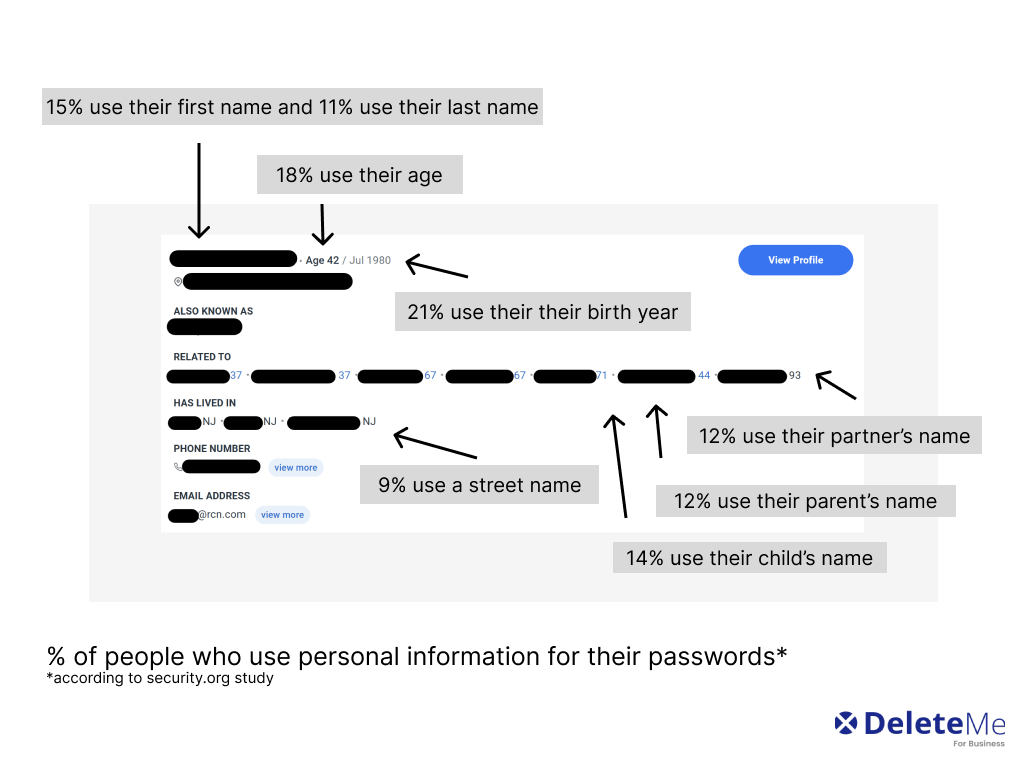

Threat actors increasingly use people’s personal information to narrow down lists of likely passwords and break into accounts. Despite years of repeated warnings against passwords like date of birth or pet’s name, research shows that people continue using password components based on personal information.

Information needed: Employee email addresses (personal or professional) and other personal information that might be used as part of a password, like their date of birth, partner’s name, street name, etc.

OSINT available: Employer websites, social media, public records, B2B data brokers, and people search sites.

Real-world example:

1 in 4 business leaders has a birthday as part of their password.

Impersonation

Impersonation scams typically involve criminals pretending to be employees to help desk support to reset account credentials.

Information needed: Employee email addresses and other personal information that might be used as answers to recovery prompts.

OSINT available: Employer websites, social media, public records, data brokers, and people search sites.

Real-world example:

Threat groups like LAPSUS$ are known to call target company’s help desk staff to try and persuade them to reset a privileged account’s credentials. Common actions here include answering recovery prompts such as “mother’s maiden name” or “first street you lived on.”

Counter OSINT: Steps Organizations Can Take to Mitigate Human Vulnerabilities for Breach Prevention

Employee information on the open web is putting companies at a real risk of data breaches.

Removing this data will not necessarily prevent organizations from getting hacked, but it will strengthen their overall security posture.

To improve employee privacy and corporate security, organizations should:

- Audit their company site for employee personal information and, where possible, remove it.

- Educate employees about the risks of oversharing on the internet.

- Offer employees data broker removal services that opt them out of some of the most popular data broker sources.

The easier it is to access company and employee data on the internet, the higher the chances that bad actors will target them with malicious campaigns. The opposite is also true. If getting company and employee data is difficult and time-intensive, threat actors will likely move onto a different target—one that is more exposed. In short, an ounce of breach prevention is worth a pound of cure!

- Employees, Executives, and Board Members complete a quick signup

- DeleteMe scans for exposed personal information

Opt-out and removal requests begin - Initial privacy report shared and ongoing reporting initiated

- DeleteMe provides continuous privacy protection and service all year

DeleteMe is built for organizations that want to decrease their risk from vulnerabilities ranging from executive threats to cybersecurity risks.

news?

Is employee personal data creating risk for your business?