The Ultimate Guide to Executive Privacy and Executive Security Online

Table of Contents

Personal information protection is essential for executive privacy and executive security.

This is because when their personal information is put online by data brokers, executives are exposed to a particularly dangerous variety of threats.

Bad actors use personal information to target executives with threats ranging from harassment and identity theft to social engineering and credential compromise.

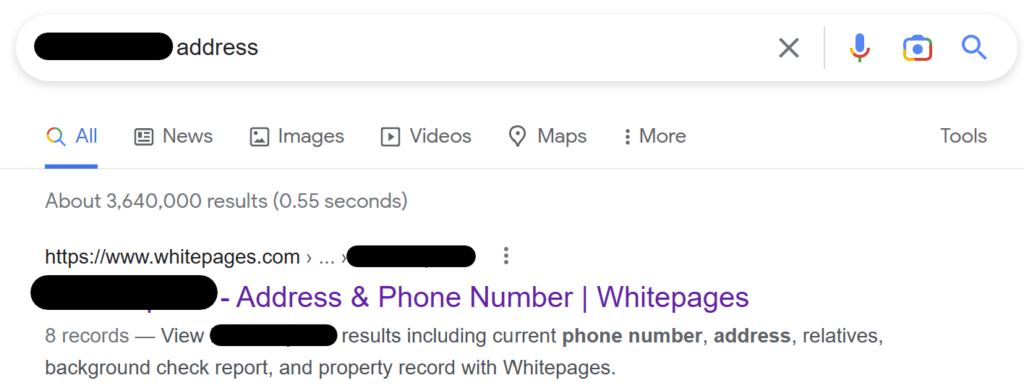

The unfortunate truth is that most of the time, executive personal information is dangerously easy to find.

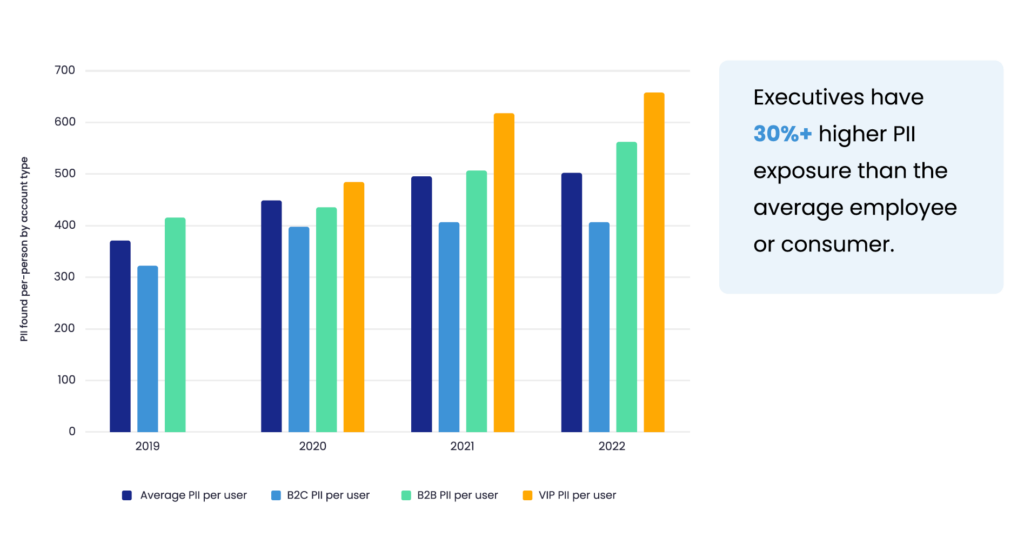

According to our research, executives have a much higher exposure rate (between 15% and 25%) on online public data sources than average employees.

To help buck this trend and keep your own or your executives’ personal information secure, this guide will show you:

- How bad actors can access executives’ personal information on the open web.

- The risks to executives that personal information creates.

- Key steps organizations can take to improve executive privacy and executive security.

Executives’ Personal Data Is Exposed Online

Data brokers are one of the largest sources of executive personal information exposure.

Data brokers are private businesses that collect personal information about executives from various online and offline sources, collate this data into a single profile, and then sell it to third parties.

Learn more: Data brokers: your comprehensive guide

Stopping data brokers from collecting, sharing, and selling an executive’s personal information is very hard to do, if not impossible.

This is because anytime a person interacts with a third party online (opens up an online account, shares a social media post, visits an e-commerce site, etc.) or offline (buys a car, gets a divorce, uses a loyalty card at the grocery store, etc.), a digital record is created.

Depending on who holds this information, a data broker can either (a) buy this data (for example, from phone companies, retailers, etc.) or (b) scrape it from freely available sources(for example, from social media platforms, forums, business listing, real estate records, state professional and recreational license records, marriage certificate records, etc.)

Data brokers continue searching these sources to collect hundreds of data points for every person on their list.

These personal information data points are then compiled into a digital dossier and sold to advertisers, marketers, and anyone else who wants to buy collections of people’s personal information. Data brokers rarely vet their customers.

This method puts executive security and privacy at particularly high risk.

Because executives tend to have public-facing roles and wider networks and are generally more valuable to marketers, far more of their personal information is findable on data broker sources than average employees.

The data available about executives on these sources also tends to be more detailed, i.e., not just directory-style data points but information on their families, hobbies, properties, and more.

This is the case for executives that work at companies of all sizes, from SMBs to large enterprises.

Mitigation is a problem too. Even when a company an executive works for has an executive security program in place, we typically still find their personal information on data broker websites.

Common information available about executives on data brokers includes:

- Full name

- Current address and address history

- Phone numbers

- Personal and professional email addresses.

- Date of birth

- Financial information, including estimated income and net worth

- Family member data

For bad actors, this means they can find everything they may want to know about an executive in a single place and with a simple Google search.

Using a data broker is far easier than scraping an executive’s social media or looking for information on public records and cross-referencing this data to make sure it’s correct.

How Data Brokers Threaten Executive Privacy and Executive Security

The proliferation of executive personal data on data broker sources has a direct effect on executive security and privacy.

Data brokers put business leaders at increased risk of personal, financial, information security, and reputational attacks.

Personal threats

Personal information exposure impacts executive security and puts them at risk of a range of threats, including harassment, doxxing, and (somewhat more rarely) swatting.

Harassment

Taking a stand on social/political issues, severing ties with clients or vendors, or making unpopular layoff decisions can all put executives at an increased risk of harassment.

For example, about a third of executives say they’ve seen an increase in physical threats and company backlash due to political unrest and racial justice activism.

Harassment that starts online or over the phone can quickly escalate, putting executive security in danger.

In 2019, a man named Rakesh “Rocky” Sharma left intimidating voicemail messages for Apple executives, indicating that he knew where they lived and threatening to resort to gun violence. A year later, a man not only left Apple executives disturbing voicemails and tagged Apple CEO Tim Cook with inappropriate photos on Twitter but also trespassed onto Cook’s property — twice.

Virtually every people search site and data broker sells executive email addresses, phone numbers, and home addresses. Some of them offer this information for free. Worryingly, it can even appear as the first result on search engines like Google.

Once they find an executive’s home address on a data broker site, bad actors can look for pictures and floorplans on real estate sites like Zillow and information on daily routines on social media platforms.

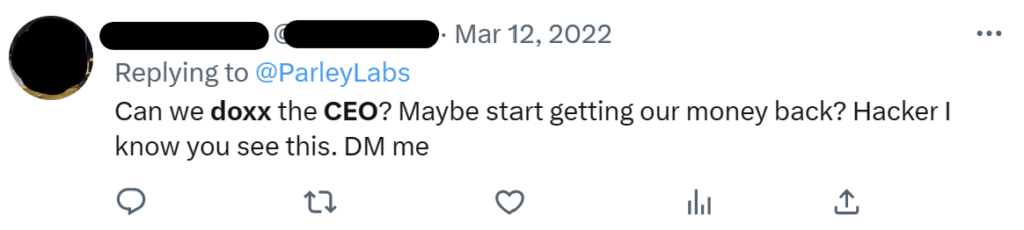

Doxxing

Doxxing, or doxing, is the act of finding and publicizing an executive’s personal information, like their home address, phone number, and even details about their family, online.

The aim is usually to embarrass an executive, draw criticism to them, or cause them physical and/or emotional harm.

In 2015, hackers leaked the address and phone number of the former chief executive officer of Turing Pharmaceutical AG, Martin Shkreli, on 4chan, an anonymous online discussion board. According to CNN, “subsequent comments suggested ordering pizza to [Shkreli’s] Manhattan apartment and sending prostitutes who demand pills as payment.”

Shkreli was doxxed because he raised the price of Daraprim, a drug used by cancer and AIDS patients, overnight.

But executive security can be threatened in this way even if they don’t do anything controversial.

In 2020, finance marketing executive Peter Weinberg was misidentified by internet sleuths who accused him of assaulting a child. His home address was posted online, and his social media blew up with messages like “we’re coming for you” and “you deserve to pay.”

Swatting

Swatting is when someone threatens executive security by tricking law enforcement into sending armed officers (and often SWAT teams, hence the name) to an executive’s home.

In 2020, pranksters swatted a number of tech executives, including senior Facebook executive Adam Mosseri.

“Officers arrived in force and barricaded the streets outside. Twice,” wrote The New York Times. “But after tense, hours-long standoffs, they realized the calls were hoaxes. There were no hostages, and no one in the homes had called the police.”

Financial Fraud

High-profile, high-income individuals typically have more accounts and credit, which puts them at a higher risk of financially-motivated identity theft.

As long as an identity thief knows enough personal information about an executive, they can trick the person they’re talking to into thinking that they’re who they say they are.

Learn more: Privacy vs. identity protection: what’s the difference?

Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen’s identity was stolen after an identity thief called his bank and, pretending to be Allen, changed his address and phone number. He later called the bank again, this time convincing the employee to send him a new debit card in Allen’s name.

These kinds of incidents happen all the time.

A few years ago, a man was able to open bank accounts in other people’s names and collect nearly $200,000 in fraudulent loans from six different US banks after buying a swathe of personal information from a data broker.

Information security risks

Cybercriminals often target executives in cyber-attacks because they tend to have admin privileges and, as a result, access to sensitive documents, databases, and other valuable materials.

Most business leaders understand the importance of cybersecurity. Yet many executives circumvent security safeguards if it makes their life easier.

Two main executive security threats are social engineering and account takeover. Although less talked about, corporate espionage via social media sites like LinkedIn is becoming more common.

Social engineering

Over a third of surveyed executives admit to clicking on a social engineering link. This is four times the rate of a general employee.

Two types of social engineering attacks affect executives specifically:

- Spear phishing involves sending personalized emails or text messages to executives to trick them into revealing confidential information or installing malware on their devices.

- Whaling (also known as CEO fraud) is when cybercriminals send deceptive email messages pretending to be senior executives at an organization to other executives or third parties like clients.

In both cases, attackers use data brokers and other online sources to both (a) find targets and (b) make their messages seem more authentic.

It is not enough to know the names and email addresses of executives. Cybercriminals also need to find “the missing detail” that will lull executives into a false sense of security and into doing what the email/text message asks them to do. This requires cross-referencing lists through sources like social media, corporate websites, and data brokers.

Back in the day, this used to be an arduous process. Today, it’s easier than ever, thanks to open-source reconnaissance tools.

Learn more: 3 personal information insights to help companies protect themselves against hackers

Because many online data sources include information on family members, cybercriminals can also target an executive’s partner, child, or parent, gain access to the executive’s home network, and look for other assets to leapfrog to.

These attacks are made more dangerous because many employees access data that belongs to their employers on personal devices. Additionally, a large number of board members and executives use personal email addresses for business purposes. Threat actors, including the Chinese hacking group APT31, are known to send phishing emails to Gmail users.

Learn more: How cybercriminals use open-source intelligence for social engineering

Successful social engineering campaigns can have devastating consequences for both organizations and executives themselves.

In 2018, the CFO and Managing Director of Pathe, a European cinema chain, were fired from their jobs after failing to spot a whaling attack that cost their company more than $20 million. The same thing happened to the CEO of the Austrian aerospace parts maker FACC.

Account takeover

C-level executives like CFOs and CEOs are twice as likely to be affected by account takeover attacks compared to the general workforce.

Account takeover (or account compromise) happens when cybercriminals gain access to an executive’s online accounts, usually through credential stuffing.

Additional security measures like executive security questions and multi-factor authentication rarely stop determined attackers from taking over an executive’s account, as these can also be bypassed.

Credential stuffing

Most people tend to think of credential stuffing as a “dumb” attack where hackers use breached data sets to infiltrate target networks. In reality, cybercriminals also make use of personal information available on the internet to take over accounts.

Many people use easy-to-remember passwords derived from personal data, and executives are no exception. About one in four executives use birthdays as part of their password.

These kinds of weak passwords are a problem because if a threat actor can find out enough about an executive, they can conduct targeted password-guessing attacks, and impact executive security.

Learn more: The link between weak passwords, data breaches, and data brokers

In the past, leveraging executive personal information for account takeover attacks was a relatively complicated and time-intensive process. There was just too much personal information to go through, and at least some of it was erroneous or outdated.

The widespread availability of open-source tools and AI has meant that cybercriminals can employ this tactic at scale.

Meanwhile, sophisticated bots allow hackers to hide their activity from security controls designed to detect brute force attempts.

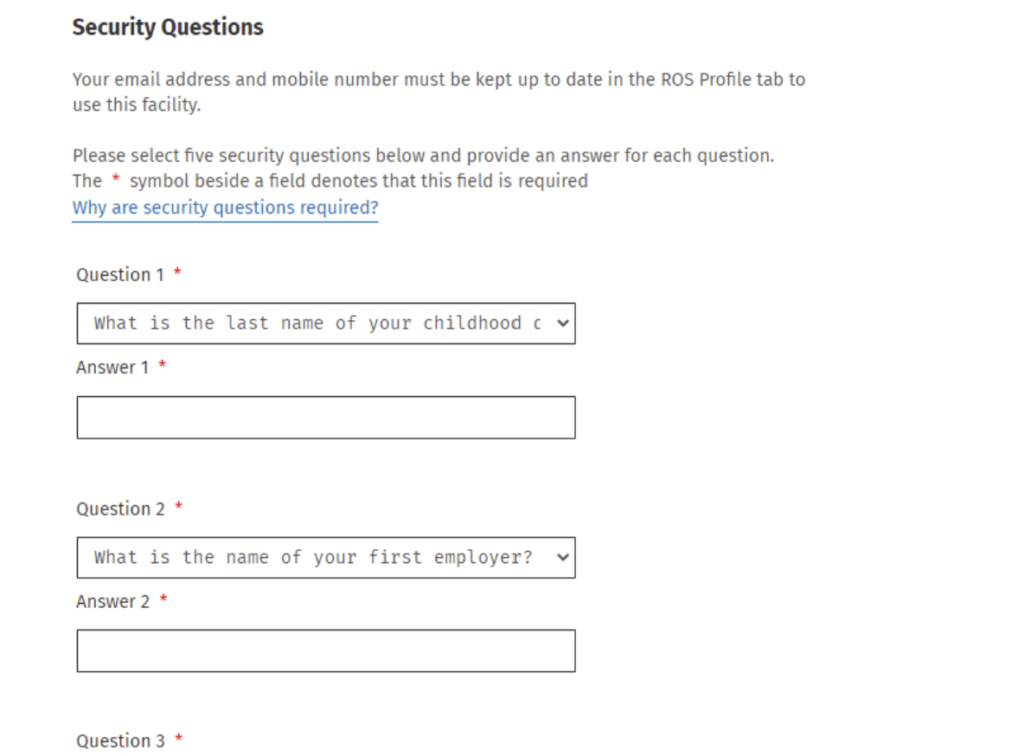

Security question guessing

In addition to requiring a password, some login portals also ask for executive security questions. Others let executives reset a forgotten password by answering questions like “what city did you grow up in?” or “where did you go to high school?”

Knowledge of personal information can help cybercriminals circumvent executive security questions.

Despite their name, answers to most executive security questions are far from secret. For example, most people’s mothers’ maiden names (a common executive security question) can be found via marriage and birth records. This information also appears on data brokers, which makes it easy to compromise executive security.

MFA bypass attacks

Multi-factor authentication doesn’t guarantee executive security. Criminals can bypass between 90% and 95% of MFA solutions using a phishing text, email, or phone call.

As security researcher Kevin Beaumont said, “call the employee 100 times at 1AM while he is trying to sleep and he will more than likely accept it.” This is known as MFA fatigue, and is a tactic that was used to breach Uber.

SIM swap attacks, where an attacker takes over an executive’s phone number by impersonating them to their phone company, are also a popular way to compromise executive security.

Corporate espionage

Easy access to executives’ personal information makes it easy for competitors and adversaries to conduct corporate espionage.

A good example of how this might happen was shared by the risk management expert Lisa Forte in a Darknet Diaries podcast episode.

She recounted how a scientist working at a particular company wrote a fairly benign LinkedIn post that was commented on by a woman with a very similar background to him.

They began communicating, and before he knew it, he had:

- Shared his organization’s intellectual property with her (she had promised him a better job but apparently needed to see proof of the projects he had worked on).

- Clicked on a malware-laden link (she said her HR department would send him documents he needed to read).

An investigation into the incident could not determine who the threat actor that duped the scientist was. It could have been a nation-state hacker, competitor, or someone else with an agenda.

However, one thing is clear: the threat actor went to great lengths to make their LinkedIn profile look similar to their target’s.

To do this, the threat actor could have gleaned some information from the target’s LinkedIn profile, but they could have also found additional information they needed from data brokers, who not only scrape social media but also get data from other sources, like public records and credit card companies.

Corporate espionage on social media platforms like LinkedIn is becoming a more serious problem. Intelligence and security services across the world are warning organizations to be on the lookout for fake LinkedIn profiles that are likely connected to nation-state threat actors.

Reputational attacks

If a bad actor can successfully impersonate an executive, they can negatively impact that executive’s reputation. This can also damage the reputation of the company the executive works for.

For example, an attacker that impersonates an executive in a fraudulent email that goes out to a client or business partner could ruin the executive’s (and the company’s) relationship with the recipient.

The same can happen if a bad actor creates a fake social media profile in an executive’s name using personal information found on online sources.

In a social media impersonation attack, a bad actor can use an executive’s name to defraud unsuspecting individuals, post negative commentary directed at a group of people or organization, or share fake updates about the company they work for.

Bad actors tend to like social media impersonation attacks because social media gives them a wider audience.

In one real-world example, an executive was impersonated on Instagram. By the time he found out about it from a friend who texted to ask him if he had reached out to him on the social media platform, the account had 2,300 followers.

Who Needs Executive Security Protection?

It’s not just business leaders who need executive security protection and digital privacy services. Their families can be at risk too.

Because data brokers make connections between individuals, an executive’s data broker profile can often contain information on their spouse, kids, parents, and other family members.

This can increase both personal and organizational risk:

- Personal risk. In the wake of controversial events, there is a higher risk of doxxing for public-facing figures and their family members. For example, at least two LAPD officers saw information on where their kids go to school posted on the internet.

- Organizational risk. In several cases, advanced threat actors sent phishing texts to employees’ family members in an attempt to gain unauthorized access to companies’ internal systems.

Board members and other high-risk individuals (including highly visible employees) and VIPs, like those with high levels of access to sensitive corporate data, are also often targeted in personal and corporate attacks and can benefit from executive security services.

How Organizations Can Protect Executive Security and Privacy

Depending on the size of the company, assessed risk, and security needs, executive security services can cost anywhere between $50,000 (small organization) and $1 million (large Fortune 500 firm) per person.

This cost often includes executive security tools and services like like email monitoring, social engineering training, security guards, key person insurance, and executive protection agents.

While crucial, these kinds of corporate executive security systems are reactive, i.e., they help executives and their teams spot and stop attacks in progress.

To make attacks that compromise executive security and privacy less likely to happen in the first place, another layer of defense is needed: proactive personal data removal.

Personal data removal reduces the amount of personal information that appears about corporate executives on the internet. It involves opting out of popular data broker sources to ensure that when a bad actor googles an executive’s name, they can’t view their entire life’s story.

To work, opt-outs need to be continuous. Data brokers relist people’s profiles as soon as they scrape/buy new data.

Executives rarely have the time to keep on top of regular, manual opt-outs themselves. That’s why data broker removal services like DeleteMe exist. To give executives peace of mind that easily exploitable personal information is off and will stay off the internet.

In addition to opting out of data brokers, executives and their executive security teams should take other steps to reduce their digital footprints:

- Avoid sharing personal life on social media, especially on professional accounts. Keep personal accounts private.

- Do not include sensitive personal information in executive biographies on company websites or elsewhere.

- Provide continuous training programs to executives on the importance of online privacy.

The less personal information exists about executives on the internet, the harder they are to attack. To quote one anonymous hacker, “Whenever the target can’t be hacked well… ya know, there’s plenty of other targets out there :)”

- Employees, Executives, and Board Members complete a quick signup

- DeleteMe scans for exposed personal information

- Opt-out and removal requests begin

- Initial privacy report shared and ongoing reporting initiated

- DeleteMe provides continuous privacy protection and service all year

DeleteMe is built for organizations that want to decrease their risk from vulnerabilities ranging from executive threats to cybersecurity risks.